Justice in the World

You cannot have faith without justice

By Fr. Bill Ryan, S.J.

March/April 2013

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

In 2011, the 40th anniversary of the 1971 Roman Synod document Justice in the World passed by in silence in the official Church. Only a few ardent social justice voices noted this anniversary and asked: Why was there no celebration? The Vatican often uses anniversaries of an important encyclical or statement to re-emphasize the document’s teaching. Seven years earlier the same voices asked: Why was this significant document omitted from the Compendium of Catholic Social Doctrine issued in 2005 by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace?

At the 1971 Synod, which was devoted to the obligations laid on the Church by the Gospel to hunger and thirst—and act—for justice, 94 percent of the bishops affirmed Justice in the World. Pope Paul VI approved this still timely document on social justice and it was discussed widely in the Church and in the public forum, both favourably and critically.

Justice in the World

challenged the Church

to make an examination of her

own life and practice in order

to be able to give credible

witness to her teaching on

justice.

The challenging core message of the document was a new, even revolutionary way of making a point that the Bible has been trying to get us to understand ever since the writing of the Book of Exodus: “Action on behalf of justice and participation in the transformation of the world fully appear to us as a constitutive dimension of the preaching of the Gospel, or, in other words, of the Church’s mission for the redemption of the human race and its liberation from every oppressive situation.” (#6) “... unless the Christian message of love and justice shows its effectiveness through action in the cause of justice in the world, it will only with difficulty gain credibility.” (#35)

Justice in the World was prophetic also in other ways. For example, it used the language of “reading the signs of the times,” and the language of liberation, solidarity and the option for the poor, although these terms were a red flag for some Catholics because they were the language of Latin American liberation theology. Also, for the first time, the statement made concern for ecology a dimension of Catholic social teaching. It was farsighted in recognizing the emerging socio-economic and political interdependencies arising from the globalizing of communications, technology, and the management of capital. And it introduced concepts of “social sin” and “sinful social structures” that had only recently found their way into Catholic social theology; the Catholic tradition had absorbed from the social sciences an enhanced awareness of the power of economic and social structures in shaping human society and culture.

Finally, Justice in the World challenged the Church to make an examination of her own life and practice in order to be able to give credible witness to her teaching on justice.

The role of Canadians

Canadians played a significant role in this Synod process from beginning to end. The Synod Secretary in Rome, Archbishop Rubin, gave the task of drafting the preparatory document to the new Pontifical Commission (in 1988 renamed Pontifical Council) on Justice and Peace. Canadian-born Jesuit Philip Land, an economist and professor at the Gregorian University, became the chief drafter. Cardinal Maurice Roy, archbishop of Quebec City, was then President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace.

At the time I was Director of the Canadian Bishops’ Office for Social Affairs and was asked to prepare, in cooperation with US theologian Father Joe Komonchak, a draft entitled “Liberation of Men [sic] and Nations – Some Signs of the Times” as a possible North and South American bishops’ response to Rome’s preparatory document for the Synod. As such it was presented at a preparatory meeting of the Inter-American Bishops in Mexico City and received enthusiastic support from the Canadian and Latin American bishops. However, the U.S. bishops were divided.

In their struggle for life, many people in the Fatoya region of Guinea, West Africa, work in artisanal or small scale gold mining, some seasonally, some full-time. Miners average .12 grams of gold per day for which they earn US$2. Women make up 50 to 70 percent of the workers and children 10 to 20 percent. An estimated 13 to 20 million men, women, and children in more than 50 developing countries are directly engaged in artisanal mining. /Credit: Development and Peace./

In their struggle for life, many people in the Fatoya region of Guinea, West Africa, work in artisanal or small scale gold mining, some seasonally, some full-time. Miners average .12 grams of gold per day for which they earn US$2. Women make up 50 to 70 percent of the workers and children 10 to 20 percent. An estimated 13 to 20 million men, women, and children in more than 50 developing countries are directly engaged in artisanal mining. /Credit: Development and Peace./

When the Synod opened on November 30, 1971, each Canadian bishop-delegate spoke in the name of all the Canadian bishops, because the core ideas of their presentations had been accepted at a previous plenary meeting of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB). Cardinals Maurice Roy and George Flahiff, Archbishop Joseph-Aurèle Plourde of Ottawa, and Bishop Alexander Carter of North Bay made up the Canadian team. Archbishop Plourde, then President of the CCCB, was elected to chair the drafting committee of the Synod.

The talks given by Bishop Carter and Cardinal Flahiff made a noticeable impact on the 210 bishops worldwide who were gathered at the Synod and also made headlines in the press, particularly in the major French newspapers Le Figaro and Le Monde. Carter’s presentation on the then sensitive issue of the abusive power of multinational corporations in poor countries won him an invitation to the headquarters of UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). And Pope Paul VI warmly congratulated Cardinal Flahiff for his intervention on education for justice.

A paragraph from Flahiff’s speech has been quoted hundreds of times by social educators and activists. In it he asks why our Church’s social teaching seems to have so little impact. He suggests that this is because we have believed that it is most important, if not sufficient, to teach a theoretical knowledge of the guiding principles of social justice. He goes on to say:

“I suggest that henceforth our basic principle must be: only knowledge gained through participation is valid in this area of justice; true knowledge can be gained only through concern and solidarity…Unless we are in solidarity with the people who are poor, marginal, or isolated we cannot even speak effectively about their problems. Theoretical knowledge is indispensable, but it is partial and limited; when it abstracts from lived concrete experience, it merely projects the present into the future.”

“The Church cannot be deaf or mute before the entreaty of millions of persons who cry out for liberation, persons oppressed by a thousand slaveries. Those who put their faith in the Risen One and work for a world more just, who protest against the injustices of the present system, against the abuses of unjust authorities, against the wrongfulness of humans exploiting humans; all those who begin their struggle with the resurrection of the great Liberator—they alone are authentic Christians.”

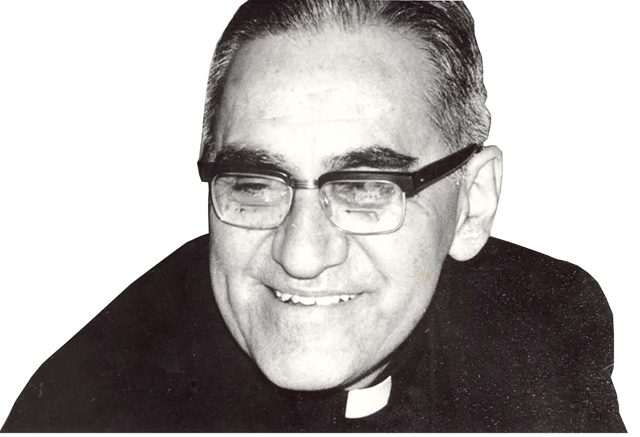

Archbishop Oscar Romero, a defender of the poor in El Salvador, was murdered in the act of celebrating the Eucharist. March 24, 1980.

The final statement of Justice in the World has had more circulation and influence, especially in North America, than any other statement of a Roman Synod. For example, in the decade following the Synod, the Canadian bishops issued 25 social statements—most of them applying to particular situations and issues such as unemployment, technology, and disarmament—affirming the principle that faith and justice are inseparable. These Canadian Church statements were deliberately echoing the Synod’s teaching that the doing of justice is a constitutive, essential dimension of preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Religious congregations in North America used Justice in the World extensively to educate their members in Catholic social teaching. Congregations of Sisters applied its principles as they promoted the role of women in the Church and in society. The Center of Concern in Washington took Justice in the World as a kind of manifesto. Working out its principles as applied to Church and society, the Center published a tabloid-sized resource entitled Quest for Justice that sold more than 200,000 copies and was used widely in workshops on social justice. And in 1975, when a General Congregation of the Jesuits decided after 13 weeks of discernment to describe their mission in the present age as, inseparably, “the service of faith and the promotion of justice,” the Decree expressing that conviction quoted resoundingly from Justice in the World.

Why no celebration?

So why hasn’t that fruitful document been greeted with grateful celebration on its 40th birthday either in Rome or in Canada? Has the disagreement concerning some of its ideas or wording, felt in some networks from the moment of its publication, won out over the conviction of the bishops gathered in 1971?

Some commentators think that the practical recommendations made in Justice in the World explain why Rome does not want to draw attention to the document 40 years later. One such recommendation urges that a high level commission be set up to consider the future role of laity—especially of women—in the Church and in society. Others think that the use of terms from liberation theology still jars some people in Rome.

In recent decades the Church has been pressured by the highly publicized scandal of sexual abuse by clergy. Some think Church leaders are embarrassed. Justice in the World pointed out, of course, that the Church should make a serious examination of its own lifestyle and practices to ensure that it gives a genuine witness to what it presently preaches on justice.

Do these difficulties explain the absence of attention to Justice in the World on its 40th birthday? Partly, perhaps. Add to that the fact that Canadian culture has been shifting to the right and enthusiasm for social change is much less popular than it was in 1971.

On the Vatican level, there has been a de-emphasis in recent years on collegiality and thus on the magisterial significance of synods of bishops. In the theology of Pope Benedict Roman synods, like episcopal conferences, do not have the ecclesial stature that Vatican II and Pope Paul VI seemed to have been willing to give them. Archbishop Maxime Hermaniuk of Winnipeg argued bravely at several Synods that such gatherings should be seen as deliberative, not merely advisory.

Whatever the case, we as Christians must continue to live a faith that does justice, strengthened by the 1971 Synod’s conviction that “action on behalf of justice and participation in the transformation of the world fully appear to us as a constitutive dimension of the preaching of the Gospel.” Surely that fundamental conviction deserves a central place in the Church’s 21st century understanding of what it means to evangelize the world.

Fr. Bill Ryan is Special Advisor to the Jesuit Forum for Social Faith and Justice in Toronto. As the for-mer Director of Social Affairs for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, he was involved in the founding of the Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace. He was the founding Director of the Center of Concern in Washington, DC, and he also served as Jesuit Provincial for English Canada and as General Secretary of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. The above is an abbreviated version of an article in the April/May 2012 issue of Open Space, a publication of the Jesuit Forum for Social Faith and Justice, www.jesuitforum.ca. Reprinted with permission.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article