ABORIGINAL Spirituality

By Paul McKenna

April 1993

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

(An interview with Reverend Laverne Jacobs)

Reverend Laverne Jacobs

If you were to consult an encyclopedia of religions, you would learn that the oldest of the world's religions is Hinduism, dating back some 5,000 years. This conventional wisdom, however, is not really accurate. Aboriginal spirituality - the religion of Native people - is in reality much more ancient.

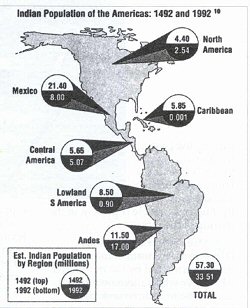

For thousands of years Native people have inhabited many parts of the globe. Canada's Native people, for example, have been here for at least 12,000 years. Some archeologists claim that aboriginal people have inhabited the Americas for more than 30,000 years.

So why, we must ask, has the world's oldest religion been ignored by the traditional purveyors of religious knowledge. Part of the explanation has to do with the expansion of European colonial interests throughout the world beginning with Christopher Columbus in 1492. The European Christian missionaries who encountered the Native people failed to take the aboriginal religions seriously or to see God's presence in them.

In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in Native spirituality and a new confidence among aboriginal peoples. Many Native people (both Christian and non-Christian) are struggling to reclaim their ancient traditions.

Reverend Laverne Jacobs is an Ojibway Indian and an Anglican priest. A member of the Walpole Island Reserve near Wallaceburg, Ontario, Reverend Jacobs has served as pastor to both Native and non-Native congregations. For the past five years he has functioned as national coordinator for the Council for Native Ministries within the Anglican Church. The Council is a body of Native people that gives direction to the Anglican Church.

Scarboro Missions magazine approached Reverend Jacobs " with three central concerns:

- 1) What is aboriginal spirituality?

2) How are he and other Native Christians struggling with the fact that they have roots in two great religious traditions, and

3) What is the significance of Native spirituality for non Native Christians and the larger Church.

SM: What in your opinion, are some of the chief characteristics of aboriginal spirituality?

Reverend Jacobs: First of all, you have to realize that in Canada there are many First Nations (tribes), each with different customs, traditions, cultural practices and spiritualities.

The word "relationship" is key to understanding the Native worldview and Native spirituality; or to be more specific, the word "interrelationship. " Indian people have a deep sense that all facets of creation are interrelated, are in harmony with one another. This sense of relationship extends to the land, the earth, the birds, the animals, to our sisters and brothers and to the Creator.

Connected to this sense of interrelationship is a deep sense of respect for all parts of creation. We honour all that the Creator has made. Our sense of respect for creation is related to other key Native values: stewardship (care) for the environment, the importance of community, the notion of generosity and sharing, respect for the teaching of our elders, and humility. Native people have a profound sense of respect for the Creator. God is very real for the Native person. Generally speaking, Native people relate to their Creator in a way that is very personal, very open, very natural. Their relationship to God is thus more emotional than intellectual.

SM: These qualities, these common themes, are they universal among Native Peoples? I mean, do you find these common themes among aboriginal peoples in other parts of the world?

Jacobs: Yes, I would say so. Generally you can find these same patterns among Native Peoples around the world. Particularly this concept of the interrelationship of all parts of creation and this ability to be open to experiencing God in a deeply genuine and deeply personal fashion.

SM: Is the notion of a relationship to the land a fundamental value in Native spirituality?

Jacobs: Yes. To get a sense of how Native people value their relationship to the land, it's helpful to look at what happens to them when they are displaced from the land. Being separated from their land can literally break them - their souls, their will to live - and they become a very dysfunctional community. We can see this happening in Canada and in other parts of the world as well. To give you an example of what I'm talking about, let's look at the effects of the huge development projects in northern Canada. Here it's not just a question of the destruction of the land or the environment or the animals, but also of people's wills and souls.

For Native people there's a real sense in which the land, the earth, is Mother... When Native people hunt and kill an animal, for example, they pray for it, as a way of giving thanks that this animal has offered its life. In the Native view, some animals must be killed in order for us to live... There is a belief among aboriginal peoples that you take from nature only what is needed. And you don't take something from creation without somehow replacing it.

And this sense of stewardship for the land and for all creation extends not just to the present generation. In the native view there is a commitment to safeguarding the environment for generations to come.

"Each people preserves and expresses its own identity and enriches others with its gifts of culture, tradition, customs, stories, song, dance, art and skills. I encourage you to keep alive your language, your culture, the values and customs which have served you well in the past. These things benefit not only yourselves but the entire human family." - Pope John Paul II - Native gathering in Phoenix, Arizona,1987

SM: In the Christian world view, the human person is the centre and focus of the divine plan. Or in the words of Teilhard de Chardin, "man is the peak and crown of creation." Native spirituality, on the other hand, emphasizes relationships of interdependence and reciprocity between all forms of creation. Accordingly, in the words of the great Sioux chief, Seattle, "the earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth." Your comment?

Jacobs: I have a lot of difficulty with that statement of Teilhard de Chardin's. I have real difficulty with claims that humans are more important than other creatures or other parts of creation. To come back again to this sense of the interrelatedness of all life, the sacredness of all life; if you listen, for example, to the Native prayers of thanksgiving for the Mother (Earth), for the birds, for the flowers, if you listen to these prayers, there's no sense of humans being above the other creatures.

In the aboriginal scheme of things, we humans don't stand outside nature. We are nature, i.e. we are part of nature, not apart from nature. And you can find some of these same values in the teachings of Christ, many of his teachings came from nature. He instructed his disciples how to live given their dependence on nature.

SM: Why do non-Native people have trouble understanding Native people?

Jacobs: Native people as a whole are fairly content to just be. I guess you could say that they have a kind of contemplative nature about them, and non-Native people seem to have a great deal of difficulty with this. Non-Native people can't seem to feel good about themselves unless they're doing something. They have to have an agenda... It seems to be very difficult for them to sit idle and just be... One's value, it seems, is wrapped up in what one has accomplished, in what can be materially measured.

For Native people, the key is relationship. It's okay just to be present to people. Native people don't tend to dominate but rather to listen, to respect other people's presence. It's not so important whether one has accomplished this or done that.

And so, one can see here that there are two different perceptions, two different behaviour patterns, two different value systems.

SM: In recent years, there has been a renewal of interest in Native spirituality. When and how did this happen?

Jacobs: In terms of a time frame, I would locate this development in the 1970s. The crisis of identity among Indians has lead many of them to search out what does it mean to be Indian. Native people were struggling to discover who they were. They began to re-examine and rediscover their roots, their traditions - traditions such as Native dances, symbols, myths and powwows, etc.

All of this amounted to what could be called a "pan-Indian movement". Much of its energy and initiative has come from western Canada where the Native traditions have been kept alive. This is because tribes in the western part of our country have traditionally had less contact with western Christian society.

The first phase in this process of Native self-discovery involved a cultural search - a search for the meaning behind these traditions, symbols, dances, etc. But then there occurred a shift: people began to delve into traditional Native spirituality, into such rites as the sweetgrass purification ceremony, the eagle feather, the pipe and others...

• The Sweetgrass Ceremony is a rite involving the burning of Sweetgrass as a sign of cleansing or purification. The ceremony is being performed more and more because it is the least threatening of the various Native rites and because more and more people have permission to use it.

The Sweetgrass ceremony is sometimes performed at the beginning of meetings and religious services. Sometimes it is used in much the same way that incense is used. In the context of the Eucharist, for example, it can be used to incense the elements.

Elements for a Pipe Ceremony: the sacred pipe, carrying pouch, medicine hundles, tobacco role

• The Pipe is a very important symbol in Native culture, almost the equivalent of the Christian sacrament. The sharing of the pipe between people is considered a very sacred act, regarded with the same respect as communion. And for some people in Native Christian culture, the pipe has actually come to symbolize Christ. For just as Christ is actually present in the Eucharist, so He is present in the sharing of the pipe.

• The Prayer in the Four Directions is a form of intercessory prayer performed by the individual who prays while alternately facing each of the four directions: east, west, north, south. The pipe and the sweetgrass ceremony are sometimes used with this prayer.

• The Eagle Feather is one of the highest signs of honour that one can receive within the Native community. Its symbolic power is related to the fact that the eagle flies higher than the other birds. The feather therefore represents God's power, transcendence and strength. Sometimes the feather is passed from person to person in community gatherings. It's also used to fan the fire of the sweetgrass and to blow the smoke. Clergy sometimes use the feather when they give a sermon or make the sign of the cross.

SM: Could you comment on some of the similarities and differences you see in the Christian and Native traditions? For example, how is God perceived in each tradition?

Jacobs: In the western Christian tradition, God, it seems to me, is perceived largely as a father figure who is all powerful. And the whole issue of morality is very much tied up with the western Christian concept of God. In the Native tradition, God is neither male nor female. God is God.

In western Christian thought, a lot of words and definitions and creeds are used to describe or define the reality of God. Native people feel less compelled to define God. God is seen as more of a mystery, the source of all life.

In my perception there are two fundamental qualities that characterize aboriginal spirituality: first, the interrelationship of all parts of creation, and second, an approach to God that is very genuine very open and very personal. And, in my view, this approach to spirituality differs greatly from that of non Native people.

SM: Could you elaborate upon this second quality of aboriginal spirituality, and how it differs from western Christian (or non Native) spirituality?

Jacobs: When I think of spirituality I think of how people live and how they respond to different circumstances. Native spirituality is a way of life. There's something about Native people, a quality that is difficult to describe: life and death and God are very real for aboriginal people. Their spiritual world is very real.

Native people seem to have an ability to be open to God and to experience God at a deeply personal Elements for a Pipe Ceremony: the sacred pipe, carrying pouch, medicine bundles, tobacco role level. Their relationship to God is really quite emotional, whereas I find that non Native people deal with God in a more analytical or intellectual fashion.

What is true for Native people is also true, in my experience, for Third World peoples and ethnic peoples. These peoples tend to talk more openly, directly and plainly about how God acts in their lives. This is one of the major differences I see between the theologies of these peoples and the theology of western Christians. And there is quite a difference in how both groups describe and live out their theologies.

This difference in depth between the two spiritualities really became clear to me when I served as pastor to both a Native and non-Native parish. In my experience, Native people really walk with God in a profound way. They know God and the reality of God and they are not afraid to share that experience, including the experience of their own sinfulness. But for non-Native people the experience of God seems to be more superficial - they tend to talk about God.

SM: If you are correct in your perception that non-Native spirituality tends to be more superficial, what is your guess as to why this is so?

Jacobs: I think it's symptomatic of something lacking in western culture; but it's difficult to pinpoint whereit stems from. As a whole, people in this culture really are afraid to allow themselves to be vulnerable, to talk about feelings. People are afraid of intimacy, afraid of getting close to others; and of course this fear of intimacy with other people is connnected to a fear of intimacy with God.

Western culture has lost its sense of mystery. In this culture everything has to be controlled, defined, measured. There's no room for mystery. And God is mystery!

"The early encounter between your traditions and the European way of life was an event of such significance and change that it profoundly influenced your collective life even today. That encounter was a harsh and painful reality for you. The cultural oppression, the injustices, the destruction of your life, your traditional societies must be acknowleged." - Pope John Paul II - Native gathering in Phoenix, Arizona,1987

SM: Do you see ways in which Native spirituality can enrich non Native people (including non Native Christians)?

Jacobs: I think that non-Native spiritual experience would be much more profound and much more enhanced if they could somehow learn to share in the depth of Native people's spirituality... For example, an appreciation of the land and the sense of the interrelatedness of all facets of creation. An important Native value is the idea of community, of living together, and western society really has lost a sense of community.

SM: Some people argue that Native spirituality is pantheistic (worships nature) while Christianity is monotheistic (worships one God). Your comment?

Jacobs: This perception reveals a misunderstanding on the part of non-Native people. Some Christians think that Native people pray to animals, the earth, plants and winds, etc. The real truth is Native people are involved in a profound relationship to these elements of nature and when they pray they give thanks for them. The Native religions are monotheistic in that they believe in one God - the Great Spirit - who created all things.

SM: What similarities do you see between these two religions - Christianity and the Native tradition?

Jacobs: Both traditions believe in the omnipotence of God who is the source of all life.

On a moral or ethical level there are some remarkable similarities between the two religions. The notion of relationship is central to both the teachings of Christ and the traditional Native teachings. Accordingly, both religions share common values: respect for others, unconditional love, service, generosity, humility and forgiveness. And as I mentioned earlier, Jesus used examples from nature to demonstrate how we are to live given our dependence on nature. But the major conflicts or differences between the two religions are related not so much to ethical teachings but rather to the cultures or traditions out of which each religion emerges. For example, the cultural form of Christianity that the missionaries brought to Canada from western Europe in the 17th century was in sharp contrast to the cultural values they encountered here among the Indians.

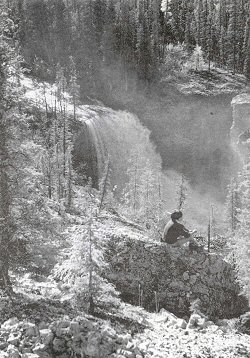

Fossil Lake River near Radeli Ko (Fort Good Hope), North West Territories

SM: You are both a Native person and a Christian. Could you share with us how you struggled with these two identities as you were growing up and how this struggle has evolved in your adult years?

Jacobs: My struggle with being both Native and Christian has always been for me a struggle to discover who I am, a question of identity... particularly during my growing up years when I went through a painful struggle to accept myself as an Indian.

During my teen years, I experienced a lot of pain and struggle about being Indian. This had to do with the fact that there was a lot of tension between the reserve where I lived and the local white community. Also, on the reserve there were a lot of social problems (e.g. drinking). Many people of my generation really had to struggle with the stereotype of the "drunken, irresponsible Indian". I felt very much ashamed of the environment I saw around me and I really didn't want to associate myself with that at all.

So as a young person I decided that I was going to run away from all that pain. In many ways I blamed my own people for the kind of pain I was in. And I decided I was going to get an education. That was my way of running away. And it was my intention never to return to the reserve.

SM: What about the Christian part of you? How did it emerge during all this turmoil?

Jacobs: At a certain point in my growing up I made a deep personal commitment to God to be a Christian. This commitment had a transformative effect upon me; it helped me to come to grips with who I was as a Native person. I could, for example, look at the letters of St. Paul or other New Testament teachings and there learn that we are all children of God. In this relationship with God, we become equal sisters and brothers in Christ. As a Christian, then, I gained a status I didn't have as a Native person - a sense of acceptance and equality.

Then, after I had been ordained for a while, something most interesting happened. My bishop transferred me back to minister to my home reserve.

Theologically, I now realize that I was being called to go back to that community and deal with the issues I had run away from - to be with my people and to learn to accept them; and in the process to face up to my own identity as an Indian. And this is exactly what happened. When I finished my ministry on the reserve a few years later, I left the community with a sense of having been healed.

So, all this was part of my identity struggle - learning who I was. Later on in my journey I began to be aware of the resurgence of traditional Native spirituality.

SM: What can non-Native people do to support Native people?

Jacobs: First of all, I would urge them to learn to "walk with" Native people. At certain times this may mean learning to become better listeners, at other times it may involve a openness to taking direction from Native people.

It's really important to us that non-Native people become educated about Native issues. Solidarity from within the non-Native constituency is really what's needed to bring about change.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article