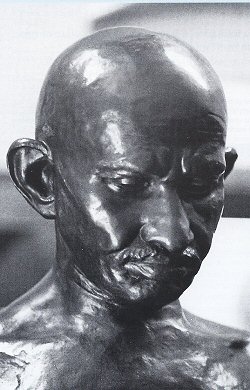

Mohandas K. Gandhi

Soldier of Nonviolence

By Paul McKenna

April 1995

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

Mohandas Gandhi

More than 500 books have been written about the life and thought of Mohandas K. Gandhi. Yet any author who struggles to depict this most extraordinary individual is faced with a conundrum because Gandhi, a person of seemingly great contrasts, continues to defy anyone's efforts to categorize him. Here was a man who campaigned for freedom by asking his political opponents to put him in jail; here was an intensely joyful man who instigated a movement based on suffering, even suffering without limit; a fervent Indian nationalist who refused to take unfair advantage of his British rulers; a born peacemaker who was also a natural fighter; a seeming socialist whose thoroughgoing commitment to economic self-reliance and local economic development made him look more like a capitalist; a man with a profound sense of the sacredness of all life but also a man who willingly and often risked his own life and challenged others to do the same; a leader whose political strategies bewildered not just his enemies but also his colleagues and followers.

These apparent paradoxes, however, start to look more like consistencies when one examines the Truths to which Gandhi remained stubbornly faithful throughout his long and eventful journey.

The Pursuit of Truth

The essence of Gandhian philosophy can be summed up in just one word: satyagraha.Using Sanskrit (ancient language of India) roots, Gandhi invented this word as a way of formulating what he had learned in his search for Truth during his struggle for the rights of Indians in South Africa. Satyagraha can be translated as "Truth-force" or the adherence to Truth in all matters." Generally speaking, satyagraha can be defined as a quiet, fervent but unyielding pursuit of Truth. The discipline of satyagraha can also be used as a technique for bringing about social justice by way of civil disobedience. But acts of civil disobedience such as boycotts, strikes and marches are an offshoot of satyagraha and not its essence. Indeed the purpose and meaning of satyagraha goes beyond the process of political liberation.

Satyagraha is comprised of three elements: Truth, nonviolence and personal sacrifice. These three pillars of satyagraha are fundamental to understanding Gandhi's philosophy.

Gandhi was filled with a passionate and lifelong search for Truth. In fact his autobiography was entitled, "The Story of My Experiments with Truth". The formula "Truth is God" was the theological principle that ruled his life and he struggled to realize that Truth through prayer and action.

The Mahatma (a name meaning "Great Soul" given to Gandhi by the masses in India) was intent on avoiding a dogmatic or rigid view of Truth because he believed that Truth and the pursuit of Truth must remain open and fluid. Gandhi came to believe that the pursuit of Truth is both a personal and universal project. Beneath the apparent conflicts and divisions of life, he argued, there resides an underlying principle of Truth, or Love; a universal principle common to the spiritual traditions of both East and West. He rejected paths to Truth that focused only on personal salvation or individual enlightenment: "the interior life of one person is not an exclusively private domain but rather a forum where the lives of all persons are made manifest: I am part and parcel of the whole and I cannot find God apart from the rest of humanity."

The Path to Truth

Gandhi was convinced that the only path to Truth is the path of nonviolence: "without nonviolence, it is not possible to find Truth." The Sanskrit word for nonviolence is Ahimsa. It is an ancient Hindu precept that expresses all the dimensions of the way of nonviolence. In Gandhian terms, Ahimsa is often translated as the refusal to do harm or injury. At a deeper level it implies a reverence for all life. Because Gandhi believed fervently that nonviolence was the supreme litmus test for Truth, he discounted any moral or religious system that failed to value the principle of nonviolence.

Ahimsa is, for Gandhi, the basic law of our being. He fervently believed that nonviolence was more natural to humanity than violence. This conviction was rooted in his confidence in humanity's natural disposition to love. Unfortunately, humans in their deeply wounded state are not fully true to their deepest inner dispositions. Therefore, they often opt for violence. Violence degrades and corrupts humans. When force is met with force and hatred with hatred, both parties descend into a state of progressive degeneration. But according to the Mahatma, this is not a natural direction for humanity. The way of nonviolence is really the natural and normal path. Gandhian nonviolence offers a methodology that is grounded in the nature of reality itself. According to Thomas Merton,

“That is why it (nonviolence) can be used as the most effective principle for social action, since it is in deep accord with the truth of man's nature and corresponds to his innate desire for peace, justice, freedom, order and personal dignity.” Nonviolence heals human persons and restores humanity to its natural state. And this includes the restoration of peace, order and social justice. This restoration of justice cannot come about through the seizure of power. Only a nonviolent transformation of the relationship between the oppressed and oppressor will generate true peace and justice. And such a relationship is impossible without an interior change in the oppressor. Prior to Gandhi there had always been individuals who practiced nonviolence as a personal or religious discipline. The Mahatma was remarkable in his ability to extend the principle of nonviolence into the realm of political struggle. Indeed his intensely personal philosophy of nonviolence became an instrument of mass protest that brought the British power in India to its knees. Gandhi believed that nonviolence was the only sane and realistic response to violence. But more than this he became convinced that nonviolence was the noblest, the most courageous and the most effective way of defending one's rights. He never doubted that nonviolence was the only hope for the modern world, the only path to unity, peace and justice. His lifelong search for meaning and Truth took place amidst intense racial, religious and political strife. And it was experience in this environment that led the Mahatma to commit himself to consistent nonviolence as a way of life. Violence in Gandhian terms refers not just to physical violence; violence involves the abuse of power in any form. The practitioner of nonviolence willingly renounces violence in thought, word and deed. Nonviolence becomes then, a total spirituality, an unconditional sacrifice, a complete way of life in which the practitioner is wholly dedicated to the loving transformation of self, of enemy and of society. In the context of a political conflict, nonviolence involves the exercise of influence in a way that brings about societal change without injury to one's opponent. To the end, the Mahatma remained convinced that Truth and the nonviolent pursuit of Truth were more powerful than guns, blows and prison bars. But there was another reason-a very practical reason-as to why Gandhi rejected violence. To his mind, violence simply did not work. In the Gandhian view, a violent resolution does damage to both parties in a conflict. Such a resolution creates an ethos of victory and defeat, a 'win-lose' dynamic between the two opponents whose relationship remains unhealed. The only legacy of violence is an endless trail of hurt, bitterness and pain. "I do not believe in armed risings. They are a remedy worse than the disease sought to be cured. They are a token of the spirit of revenge and impatience and anger." Violent change corrupts and degrades both parties. It also generates new cycles of oppression and violence, thus worsening the original conflict scenario. Gandhi always claimed that he had learned civil disobedience from Thoreau, non-cooperation from Tolstoy and nonviolence from the New Testament. In his writings he described Jesus as a model for nonviolent resistance:

"The name of Jesus at once comes to the lips. It is an instance of brilliant failure. And he has been acclaimed in the West as the prince of passive resisters. I showed years ago in South Africa that the adjective 'passive' was a misnomer, at least as applied to Jesus. He was the most active resister known perhaps to history. His was nonviolence par excellence." Gandhi was moved by the freedom contained in Jesus' teaching on forgiveness because it offers a way out of the perpetual cycle of violence.

The necessity of a moral consistency between the ends desired and the means employed is a fundamental axiom of Gandhian philosophy. Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi's longtime friend and colleague, said: "Gandhi never tired of talking about means and ends and of laying stress on the importance of the means... The normal approach ... thinks in terms of ends only, and because means are forgotten, the ends aimed at escape one... Conflicts are, therefore, seldom resolved. The wrong methods pursued in dealing with them lead to further conflict." Gandhi expressed all this in a more succinct manner: "If we take care of the means, we are bound to reach the end, sooner or later." Thus methods involving deceit and manipulation are totally incompatible with the nonviolent pursuit of Truth. Gandhi did not keep secrets from his political opponents. Secrecy implies deceit and therefore contradicts Truth. The Mahatma always, for example, informed the British about the details of his various strategies, even though the larger purpose of these same strategies was to end British power in India. For Gandhi, the pursuit of Truth is more than a personal or individual affair; satyagraha is also meant to address the corporate or universal reality. The personal search for Truth, for God, for self-realization, cannot be separated from the very public struggle for justice. Truth must be tested and lived out amidst such painful social realities as racism, imperialism and war. In the Gandhian view, a violent and unjust society is a society characterized by persistent disorder and moral confusion. At a deeper level, such a society harbours a profound orientation to un-Truth, to falsehood. The Gandhian call for freedom and justice is really an effort to name, to challenge and to unmask social un-Truths-to make them visible to all. The discipline of satyagraha is designed to bring to the surface that principle of Truth or Love that Gandhi believed lurks beneath society's conflicts and divisions. But this is no small task. To actively resist the societal forces of un-Truth and to make the Truth visible is tantamount to risking suffering, injury and even death. The satyagraha method of Truthfulness, nonviolence and suffering love involves more than an effort to make injustice visible; it is also a technique whereby the oppressed seek to convert the oppressor so that the oppressor comes into an experience of Truth, even a glimpse of Truth. And if in the process the oppressor comes to see the full humanity of the victim, violence becomes impossible. How, for example, can one mistreat, harm or injure a person whom one values and respects. As well, the oppressed are also subject to conversion in this context as one's suffering can serve to both redeem one's adversaries and also to purge oneself of hatred. By changing inner attitudes, then, satyagraha strives to transform relationships between people and also restructures the very situation that led to the original conflict. Clearly Gandhi was an idealist, but he was also a deeply practical individual who realized that one should not hold out hope for an immediate conversion on the part of one's oppressor. For this reason, he grounded his nonviolent faith in voluntary suffering without limit: "rivers of blood may have to flow before we gain our freedom, but it must be our blood." The way of nonviolence is really the way of suffering... suffering love. When the oppressor undergoes an interior conversion, this, in the Gandhian view, is actually a faith experience. Gandhian nonviolence really amounts to a method of persuasion by suffering. There are those who argue that Gandhi's approach to conflict resolution amounts to a masochistic and passive surrender to the gratuitously violent excesses of the enemy. This is certainly not how Gandhi understood it:

"Nonviolence in its dynamic condition means conscious suffering. It does not mean meek submission to the will of the evil-doer, but it means putting one's whole soul against the will of the tyrant." For the Mahatma, true pacifism was not "non-resistance to evil" but "nonviolent resistance to evil." One of Gandhi's most famous disciples, Martin Luther King, claimed that genuine pacifism is not some unrealistic submission to evil and pain; it is, rather, "a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love, in the faith that it is better to be a recipient of violence than an inflictor of it." Authentic nonviolence has nothing to do with passivity; rather the oppressed become active opponents who have chosen to lovingly resist those who will not recognize them as human. Nonviolence demands a supernatural courage, a willingness to consciously suffer without recourse to retaliation, to voluntarily risk injury, even death, and to do all this without any attachment to tangible results. In Gandhi's own words: "Just as one must learn the art of killing in the training for violence, so one must learn the art of dying in the training for nonviolence." The issue, finally, is one of bringing Truth to bear upon all matters human. The nonviolent resister is really struggling for universal Truth. Gandhi believed that, at the deepest level, the evil of violence was rooted in the lack of a living faith in a living God. Gandhian nonviolence is both meaningless and impossible without a belief in God. In fact, Gandhi felt that one could not really find God apart from the discipline of nonviolence. Between 1917 and 1948 hundreds of group satyagraha actions were conducted in India. These focused on the struggle for Indian self-rule and a number of other social issues. In strictly Gandhian terms, however, the ultimate goal of these activities was not to win a political campaign, but to service Truth. Gandhian nonviolence is about the triumph of Truth, not the triumph of power. "Gandhi does not envisage a tactical nonviolence confined to one area of life or to an isolated moment. His nonviolence is a creed which embraces all of life in a consistent and logical network of obligations... Genuine nonviolence means not only non-cooperation with glaring social evils, but also the renunciation o f benefits and privileges that are implicitly guaranteed by forces which conscience cannot accept." Thomas Merton Nonviolence - The Natural Path for Humanity

A Soldier of Nonviolence

Making Truth Visible

Suffering Love

Political Acts

Each of Gandhi's political acts can be appreciated on at least three levels of meaning. His actions in the political realm were, first of all, acts of worship. Secondly, they were symbolic events with educational purpose the Mahatma strove to bring the people of India to a consciousness of their true needs and their real situation in the life of the world. On a third level, Gandhi's acts of protest were meant as a witness to universal Truths. His many fasts, for example, were public, political acts. But they were pregnant with meaning on other levels. The fasts were acts of worship and self-purification. They were also powerfully symbolic acts of witness that were meant to bring home important Truths relevant to all persons.

Gandhi's concept of satyagraha-grounded in Truth, nonviolence and personal sacrifice-may prove to be one of the greatest discoveries of the 20th century. The satyagraha method of conflict resolution may, in fact, offer modern humanity its only way out of the current quagmire of violence that appears to be engulfing the world. Truly, the Mahatma has presented us with a path that is sane and holy, although intensely demanding.

Some observers argue that Gandhi's methods for bringing about peace and justice are naive, unrealistic and, in the end, ineffective. But when we look around our modern world and examine the 'realistic' alternatives to nonviolence, we find that they are none too many and none too inviting. This great Indian saint has pointed us another way. The path of violence, he claimed, amounts finally to "an eye for an eye, making the whole world blind."

Paul McKenna is a freelance writer specializing in world religions and interfaith dialogue. He lives in Tottenham, ON.

Resources

"Gandhi on Nonviolence", by Thomas Merton, published by New Directions, 1981. This book contains numerous quotes from Gandhi on the issue of nonviolence plus Merton's reflections on Gandhi and Gandhian nonviolence.

The Network: Interaction for Conflict Resolution, c/o Conrad Grebel College, Waterloo, ON, N21, 3G6. Ph: 519-885-0880; Fax: 519-885-0806.

Peace Brigades International, 192 Spadina Ave., Unit 304, Toronto, ON, M5T 2C2. Ph: 416-594-0429.

MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI: A Biographical Sketch

Mohandas Gandhi

- 1869 - born October 2 in a port town (Porbandar) in Western India, to a merchant caste family belonging to the Vaishnava sect of Hinduism.

- 1883 - weds Kasturbai in an arranged marriage; their marriage, until her death 62 years later, produces four sons.

- 1893 - goes to South Africa to do legal work.

- 1897-1905 - using petitions, letters and personal visits to British authorities, Gandhi challenges laws discriminating against Asians.

- 1906-1907 - addresses a mass meeting of Indians in Johannesburg who take a solemn oath to nonviolently resist unjust laws.

- - changes lifestyle by committing himself to simple dress (loincloth), lifelong celibacy, manual labour, poverty, communal life (ashram), dietary restrictions and other ascetic practices.

- 1908-1914 - jailed several times; using fasts, strikes and mass protests, Gandhi hones his skills in leading masses of people in acts of nonviolent direct action (satyagraha)

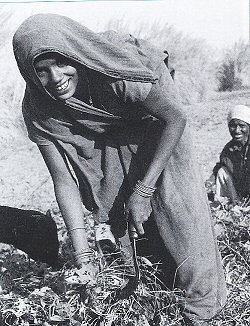

- 1914 - leaves South Africa forever and returns to India; spends one year touring India to grasp the day-to-day struggles of the poor masses.

- 1915 - sets up ashram at Ahmedabad. Ashram includes Hindus of all castes and members of other religions; community activities include manual labour, the spinning of homespun cloth and gracious treatment of animals; ashram members take 11 vows including nonviolence, truthfulness and anti-Untouchability.

- 1917-1918 - leads successful nonviolent campaigns in support of textile workers, peasants and indigo plantation workers in various parts of India.

- 1919 - As British step up persecution of nationalist dissidence, Gandhi launches Indiawide nonviolent campaign which he later suspends because of the eruption of violence.

- 1920 - elected president of All-India Home Rule League. As part of a movement toward independence and Indian self-rule, Gandhi launches a movement of non-cooperation with all British institutions.

- 1921 - leads boycott of all foreign (British)produced cloth; urges masses to produce their own homespun clothing.

- 1922 - arrested for sedition and sentenced to six years; released two years later.

- 1924 - begins 21-day "great fast" as penance for communal rioting between Hindus and Muslims.

- 1925-1929 - momentum for the independence of India grows as a result of Gandhi's influence.

- 1930 - leads Salt March to challenge the British government's monopoly over salt production; country responds with massive nonviolent action leading to the imprisonment of 100,000 people; Gandhi also arrested.

- 1931 - sails to England to negotiate with the British; scores great propaganda victory, but British government appears immovable on the issue of independence.

- 1932 - begins "perpetual fast unto death" to protest electoral discrimination against Untouchables.

- 1933-1937 - devotes considerable effort in the struggle against Untouchability.

- - inaugurates All-India Village Industries Associates; the values of economic self-reliance and the development of local skills and industries become increasingly important for Gandhi; his own ashram becomes a model for village industries.

- 1942 - leads final nationwide nonviolent campaign to urge British to leave India and is jailed for over a year.

- 1947 - August 15, India achieves independence from the British; Gandhi does not attend victory celebrations but spends the day praying and fasting to quell Hindu-Muslim conflicts that erupt in Calcutta; these conflicts broke out because Independence involved the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan (a Muslim state), a development which Gandhi had always opposed.

- 1948 - January 30, assassinated by a Hindu extremist protesting Gandhi's continued outreach to India's Muslim minority.

Part of a 1906 address Gandhi gave in Johannesburg, South Africa, to a mass meeting of Indians, each of whom took a solemn oath to nonviolently resist government laws discriminating against Asians.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article