THE STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM

Based on an interview by Christopher and Gillian David, and Tom Walsh

September 1999

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

My name is Mariano Toaza and I was born in 1944. I am a leader and founder of the Quichuan-speaking community of Pulingui San Pablo, Ecuador. Currently I am the President of FOCIFCH, a federation of 14 Native Puruhae communities that live in the Mount Chimborazo National Park.

From the time I was a child, I worked with my parents as a slave for the masters of the hacienda. From early morning until dusk we carried firewood, dug ditches, and rounded up horses, cattle, and sheep, moving them from one place to another to fertilize the land.

We received no money for our labours, and even had to pay the hacienda boss a monthly stipend for pasturing our own animals. Very often we would be out all night, following the sheep from one planted field to another. Far from our huts, we would sleep on the ground, sometimes awaking to a downpour. We would spend the day soaked to the skin and hungry, unable to change our clothes, and barefoot in the harsh climate of the mountain plateau, 12,000 feet above sea level.

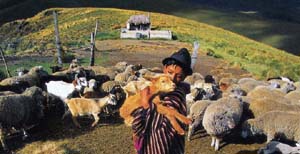

A young shepherd in the community.

Credit: Philippe Henry

We did not have enough to eat, just gruel for breakfast which had to last all day, then more gruel and a little potato at night. We drank only water and not even enough of that. There was no running water in pipes like we have now, only what we could get from springs.

On top of this the masters beat us with whips or clubs. We were held in a stranglehold by them, and by the overseer, the farm manager and even the cowman. There was nothing we could do. We suffered and there was no one to help us. We couldn't even go to Mass because we had to work all day, seven days a week.

Our huts became neglected. We had no time to mend the grass roofs. When we came home and could at last cook our gruel and potatoes, the rain would sometimes pour through into our pots, onto our plates, and soak our beds. That's how we lived; in a small hut, cooking, eating, and sleeping, without changing our clothes or being able to maintain anything.

That was our life. We lived without knowing where we were going, with no future for our children. There were schools far down in the valleys but we had no money to send our children there. So we all grew up unable to read or write, unable to defend ourselves against the police and government officials. There was no one to come to our aid.

Slaves no more

Gradually things began to change. We decided we would no longer work as slaves; we refused to continue working for the hacienda owner. In 1974 we who live high in these mountains formed an Agricultural Association.

To form the association, we united four communities: Pulingui, Tunzalao, Rumicruz, and Huararazo. The owner offered to sell us the land we now live on and after about two years we managed to raise the money and pay his asking price. We did this by collecting manure and selling it with the help of a friend who owned a truck.

Since then we have been free. We still don't have much money, just a few sheep, cattle, llamas, and horses; but things are gradually improving. Some of us have started going to school and learning to read and write. We have become more civilized.

One day perhaps we shall get help from the government, but the officials still don't know we are here and the local mayor or provincial councillor has never wanted to help us. Because our lands are within the newly created park area, authorities have accused us of destroying the unique vegetation and have threatened to confiscate our properties.

So, now we have formed a federation and can claim our rights. We believe that we can manage the park area better than the authorities if we receive support for our proposals. Their role would be to supervise our efforts.

We are a mixed community of Catholics and Protestants but in our projects we are united. We may be divided in our religious beliefs but in our work together, we are equals.

Help at last

At last help has come to us from other countries-Canada, Germany and Britain. People have journeyed here and treated us with loving kindness. They have understood our needs and have helped us to build a community centre in the village of Pulingui San Pablo, where we can all meet and our children can go to school. The Condor Centre (El Condor), as it is called, is in the shape of the giant bird. There is a meeting room in the head, workshops in the wings, a school in the body, and a health clinic in the tail.

A meeting at the new El Condor community Centre.

Credit: Philippe Henry

We make our living by growing potatoes, barley, broad beans, and other vegetables. However, when we take them to the markets, the merchants are in control. They want to buy at the lowest prices and treat us unfairly because they see us as simple, poor campesinos (peasants). What laws there are favour the rich. What we hope for now is to educate ourselves so that our lives will be improved and that one day a political leader may come from our community to work for our good and that of our children.

On the eve of the new millennium, Ecuador confronts its worst financial crisis of this century. Faced with paying 52 percent of its annual gross national product to service its external debt, the country finds itself in the unfortunate situation of being perpetually in debt to the world's wealthier nations. As citizens of lending countries, we might reflect on our role as owners of this debt and the impact it will have on people like Mariano Toaza and the communities he represents.

Christopher and Gillian David are Canadian volunteers working in Ecuador. Thomas Walsh joined Scarboro Missions in 1975. He and his wife Julia Duarte have served in Peru, Panama, Canada and now Ecuador. They have four children.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article