A Blessed Unrest

Seeking justice and working for change has become a journey of faith

By Pascal Murphy

May 2002

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

A few years ago I would have never imagined myself writing about my faith. However, I must admit that I have been consistently challenged by my faith and equally challenged by faith itself. With this in mind I would like to reflect on some of the experiences that have directed me to where I am now.

In 1995 I was invited to participate in a poverty awareness program in the Dominican Republic with my high school, St. Mike’s, in Stratford, Ontario. I must admit that my involvement in this experience was not initially motivated by the best of intentions. I had heard that it was a good time‚ and that I would be able to go to the beach and meet the locals.

Despite the fact that this program was a poverty awareness experience, I enthusiastically conjured up a tropical paradise in my mind. Needless to say, the reality I experienced in the Dominican Republic was grossly different than what I had imagined and, at the same time, it was more than I ever expected.

The local people welcomed me with open arms despite my obvious affluence, and they shared all they had. They presented me with the best food and all the hospitality they could give.

I returned to Canada challenged, and I questioned where I and my lifestyle would fit into the global picture of injustice in which extreme poverty is a widespread reality. I started searching for a way that I could contribute to creating a more just society.

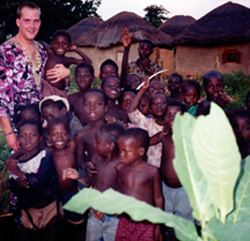

Two years later I was off on another adventure, this time with the One World Global Education Programs, to Ghana, West Africa. Once again I conjured up images in my mind of what this experience would bring to me, and again, it was vastly greater than I had imagined. Unlike the Dominican Republic experience, this time it was my faith that was being fundamentally challenged.

One experience remains with me like it was just yesterday. I was traveling down a dirt path towards the village of Cheshe—my home for the next month. Twelve of us, all close friends, were tightly squeezed into a small truck and one by one dropped off at the villages where we would be staying. Soon I was the last one in the truck.

After traveling in a completely different direction than my friends, my anxiety mounted until I was dropped at my village and left in the hands of complete strangers.

I can no longer sit idly by in my excessive comfort and not question why people are poor.

It was here that I was challenged, confronted with my vulnerability. I quickly realized that all the comforts that I had surrounded myself with in Canada were stripped away. I no longer knew how to communicate, nor what habits and customs were appropriate or inappropriate. What was safe to eat? Where could I go to the washroom? Whom could I trust? It felt like I was re-living the perplexing first steps of childhood again.

However, this process was both a blessing and a curse. My vulnerability allowed me to look at things from a new perspective and to recognize the presence of God.

There is a saying in Ghana, “God is there,” and this was the reality. I was often confronted by my vulnerability, stripped of all comfort, but God was there. I often felt alone, but God was there. And even when I denied or rejected God, God was there. I could trust God.

By the time I returned to Canada, my ways of thinking had been significantly challenged. I came back to the place where just as before, I thought I could mask my vulnerability with the comforts I had so clearly enjoyed. However, my comfort did not return. I was no longer comfortable with my excess and yet this excess was almost impossible to avoid.

On many occasions I would feel helpless because there were so many things that I had an objection to. And yet here I sit, in my more than adequate apartment, typing on my computer, securely linked to the very global reality that I have been moved to question.

When I first returned from Ghana, I adamantly rejected my own culture in order to avoid feeling responsible for indirectly supporting poverty and injustice. However, in the process of rejecting my culture I learned that I changed nothing and alienated myself from the culture I know.

Now I feel that I must embrace those aspects of my culture and its resources that make it possible for me to challenge global injustice and work for social change.

The love of neighbour that I learned from my friends in the Dominican Republic and Africa has become ingrained in my consciousness. I can no longer sit idly by in my excessive comfort and not question why people are poor.

In trying to answer this question, no explanation ‘does justice’ to such extreme inequality. Thus, I consistently find myself searching for change. This is the journey that I am on and justice is what I seek.

Reflecting on these experiences I am reminded that while my yearning for change is widely shared, my ability to actually create change is a privilege. This privilege is a gift from God and my journey of faith is to develop this gift and to use it for God’s will.

For me, living the gospel is endlessly questioning and challenging injustice and committing myself to change. My yearning for social justice has become my journey of faith and it is a blessed unrest.

Pascal Murphy is a Year III student in Social Justice, Development and Peace Studies at Kings College, University of Western Ontario.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article