Language as a tool for peace

The languages of diplomacy and conflict resolution are, above all, languages of respect

By Shahid Akhtar and Dr. Barbara Landau

June 2007

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

Language is one of the most powerful tools humans possess, with the potential to do immeasurable harm or unlimited good. In 1992, a leading international news magazine provided a perfect example of the power of language to divide and instill fear rather than to bring together and foster peace. The cover picture showed a young Middle Eastern man wearing a kafiyyah, the Arab headdress, his face almost entirely hidden except for his eyes, and holding a machine gun. The caption read, “Islam: Should we be afraid?” It was a rhetorical question that did not ask for a reply but provided one by seeking to reinforce the fear of Islam in the minds of many Western readers. This use of language has the potential of sowing seeds of distrust between Israelis and Palestinians, between Jews and Muslims, and between the world of Islam and the West. Such language creates a climate of distrust and fear in the world at large.

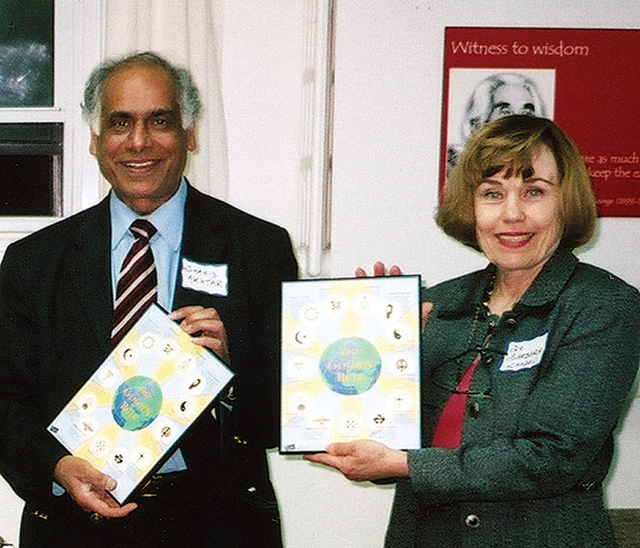

Shahid Akhtar and Dr. Barbara Landau each hold a small mounted print of Scarboro’s Golden Rule poster received as a gift. Their presentation, “Building bridges between Jews and Muslims in Canada”, was part of Scarboro’s Lenten Interfaith Series. April 2007, Scarboro Mission Centre, Toronto.

Shahid Akhtar and Dr. Barbara Landau each hold a small mounted print of Scarboro’s Golden Rule poster received as a gift. Their presentation, “Building bridges between Jews and Muslims in Canada”, was part of Scarboro’s Lenten Interfaith Series. April 2007, Scarboro Mission Centre, Toronto.

The news magazine’s use of language and cover imagery had its unavoidably negative impact, regardless of the article content, because what counts is not what the speaker said, but what the audience heard.

A few words in a caption above the picture of the gun-toting Middle Eastern man projected a powerful image in the minds of readers that effectively created a stereotype of Arabs, and later of Muslims, as violent terrorists.

It was this magazine’s choice of language that sparked the interest of the co-founders of the Canadian Association of Jews and Muslims to create a vehicle for dialogue between Jews and Muslims.

Now, many years later, the world has seen that the media and official government propaganda can use language to create conflict. The good news is that the world also knows that language can be used to create peace and harmony.

An emphasis on the language of diplomacy and conflict resolution can transform the use of language from creating conflicts to resolving them in our conflict-ridden world.

Language of diplomacy

The language of diplomacy contains attributes that in the minds of some people are equated with obfuscation, deceit and double-speak, to use Orwellian Lexicon. However, in a conflict resolution context, diplomacy is also a highly effective mechanism to avoid violent confrontations between nations. Since its origin as Lingua Franca, literally the language of the Franks, used by Mediterranean emissaries to communicate with people speaking different languages, diplomacy has successfully kept warring forces apart on a great many, though not enough, occasions.

During the Cold War years after World War II, the language of diplomacy helped the bipolar world of the Western and Communist bloc nations keep the war frozen and hope for resolution of conflict, especially in the Middle East, optimistically alive. Since the dismantling of the USSR, the emergence of a unipolar world and the events leading up to and following 9-11, a dangerous development seems to have taken place. Instead of relying on the use of diplomatic engagement, there is now a tendency among extremists of all stripes to resort to force as their preferred option for resolving serious conflicts.

It is naive to assume that all conflicts will disappear one day and the use of force will cease to exist. Yet, force must be the last resort when every humanly possible effort to deal with conflict peacefully has failed. The use of force must meet the criterion that it would make the lives of people on whose behalf it is used, better than before, not worse.

The role of the language of diplomacy is to keep the parties engaged even when the actions of adversaries may be most provocative. The language of diplomacy may end up prolonging Cold Wars, tensions, uneasy relations and even hostility between nations, but the use of diplomatic language is still better than force in achieving the intended result.

However, the language of diplomacy also needs a paradigm shift. For centuries diplomacy has been used to deal with conflicts among nation-states to avoid wars. The 21st century presents a unique dilemma. Now wars are being declared not necessarily between nations, but between nations and smaller groups, even individuals, who regardless of their small size and lack of resources, can cause damage out of all proportion.

The language of diplomacy has to meet this challenge and transform itself from a means of communication between nations to a vehicle for dealings between nation-states and much smaller factions and groups. When a war is declared on a concept like “the war on terror,” there is no nation-state counterpart with which to negotiate. The players change and with that the rules of the game. The sooner this challenge is taken up by the established political order, the more effective the world will be in dealing with potentially explosive issues through the language of diplomacy.

In the Middle Eastern context, the inflammatory rhetoric has invariably led to deplorable bloodshed, leaving the region in the grip of a vicious cycle of hateful language and brutal violence. We in Canada are not immune to this viciousness which can contaminate our communities, causing us to feel the impact of events and trends half the world away.

Conflict resolution

The Canadian Association of Jews and Muslims believes in the power of dialogue. This dialogue does not mean shouting at each other with hate. It is a dialogue that relies on language to help remove misunderstandings, stereotyping, bigotry, Islamophobia and anti-Semitism.

Despite intense disagreement between parties, the language of conflict resolution avoids threats, intimidation and bullying that may escalate hostility to the point of violence.

The language of conflict resolution is interest based, not rights based. No matter how convinced the parties may be of their God-given right to land, wealth, property and power, or of their religious views and cultural practices, using the language of conflict resolution they assume that others may have an equally strong sense of entitlement or justice. The Israeli/Palestinian conflict and the issue of gay rights are prime examples that can greatly benefit from this approach.

Conflict resolution language is the language of give and take. It avoids the “my way or the highway” approach. It challenges adversaries to be thoughtful and considerate, to take responsibility and to apply the same criteria of fairness and justice to others that they seek for themselves.

Above all, the languages of conflict resolution and diplomacy are the languages of respect. At the root of most conflicts lies the fact that someone, some group or some nation was treated differently, with disrespect and contempt. Using the language of respect and human dignity, both in religious and secular contexts, is our only hope for humanity to resolve its conflicts without destroying our planet.

Dr. Barbara Landau and Shahid Akhtar are co-chairs of the Canadian Association of Jews and Muslims.

Canadian Association of Jews and Muslims (CAJM)

Established in June 1996, our purpose is to bring members of the Jewish and Muslim communities in Canada closer together, to promote positive interaction between them, and to work together to combat problems faced by both communities.

Since September 11, 2001, we have been meeting regularly with a reinvigorated sense of purpose to create a model in Canada for Jewish/Muslim co-operation. Whatever position CAJM takes, we do it jointly and in the true interest of both groups. We may speak out on an issue, but only with agreement and understanding of members of both communities.

We are deeply committed to engaging in open and free discussion of difficult, controversial and sensitive issues. Our approach to relationship building between our communities takes place through a variety of avenues such as seminars, special events, cultural exchanges, publications, youth activities, and exchanges between speakers and community leaders. We continue to work on the goals of mutual understanding and respect and are seen as a model of cooperation between Jews and Muslims.

Contact Shahid Akhtar, T: 905-712-2872; Email: shahidakhtar1@rogers.com or, and Dr. Barbara Landau, T: 416-391-3110, Email: barb@coop-solutions.ca

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article