The vocabulary of social interaction

Words may have very different meaning sfrom one culture to another

By Fr. David Warren, S.F.M.

June 2007

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

“Asa ka man?” (Where are you going?) This was a question which I would hear many times in the Philippines when I met someone on the street. The first time I was asked this, I wanted to answer, “It’s none of your business!” I’m glad that I didn’t. Gradually I discovered that “Asa ka man?” was not a request for information as to where I was going. It was simply a greeting, a way of acknowledging my presence. In other words, “Asa ka man?” was a conventional expression.

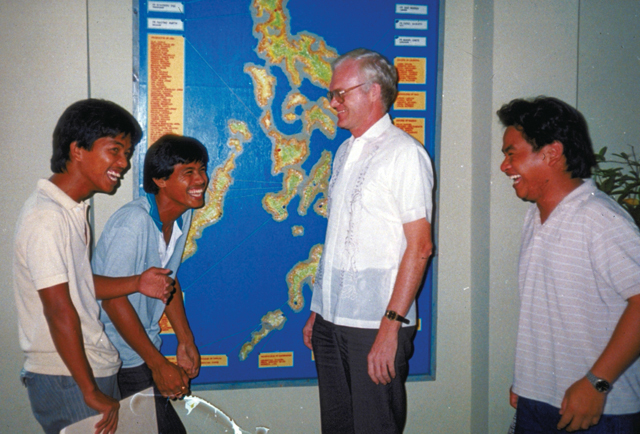

Seminarians at the Major Seminary in Cebu City, Philippines, share a laugh with Fr. Dave Warren. Fr. Dave also worked in Guyana, and has done academic studies in the field of interreligious dialogue and Christian mission.

Seminarians at the Major Seminary in Cebu City, Philippines, share a laugh with Fr. Dave Warren. Fr. Dave also worked in Guyana, and has done academic studies in the field of interreligious dialogue and Christian mission.

Each culture has its own conventional expressions. In our own culture when we meet someone we ask, “How are you doing?” We do not expect people to tell us about their blood pressure and blood sugar levels. “How are you doing?” is no more a request for information than is “Asa ka man?”.

Learning another language is not only a matter of studying grammar and vocabulary, but also of recognizing conventional expressions. For North Americans “How are you doing?” calls for a conventional answer such as, “I’m fine, thank-you.” On the other hand, to a Filipino “How are you doing?” (Komusta ka man?) is not a conventional question. Ask a Filipina “How are you doing?” and she will think that you are asking for information about her health. To a Filipino, “Where are you going?” is a conventional question that calls for a conventional answer such as “Just up ahead.” Ask North Americans “Where are you going?” (not a conventional expression) and they will be apt to think that you are prying.

In conventional expressions, the words do not mean what they seem to mean, at least to someone from outside the culture. Often in the Philippines I would be a guest in someone’s home. When the time came to leave, I would tell my host that I had to be on my way. Depending on the hour of the day, my host would say “Anhi ta maniudto!” (Why don’t you stay for lunch?), or “Anhi ta manihapon!” (Why don’t you stay for supper?), or even “Anhi ta maghigda!” (Why don’t you stay here tonight?). These were all conventional expressions with which my host was saying, “I’m happy you came and I’m sorry to see you leave.” He would have been shocked if I had said that I would stay.

A conventional expression often used by North Americans in response to a favour received is “Thank-you.” (One of the first words our parents taught us as children was “Ta-ta.”) Filipinos do not say thank you as often as we do. But this does not mean that they are less grateful or less polite than North Americans. Far from it. Filipinos will feel a lifelong obligation towards someone who does them a favour. But they express this obligation in deeds, not in words. In fact, to say “Salamat” (Thank you) seems to Filipinos to trivialize the obligation and the lifelong relationship that the favour has established between the giver and the receiver.

Conventional expressions are the vocabulary of social interactions. Without conventional expressions, we would have to think about what to say every time we interact with other people. Social life would become impossible. But conventional expressions cannot be transferred from one culture to another. One of the adventures of language learning is to recognize the conventional expressions in another culture. Words do not always mean what they seem to mean.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article