Contemporary Hermits

By Sr. Janet Malone, C.N.D.

January/February 2009

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

Going apart in silence and solitude whether full-time or in a rhythm of withdrawal and return is integral to many religious traditions and spiritualities. Hinduism’s forest dwellers, Islam’s Sufi mystics, Judaism’s kabbalists, Christian monks and hermits, each focuses the necessity of a contemplative-mystical life of simplicity, detachment, and selfless love. Each group has its models, gurus, saints, whose lives exemplify different rhythms of silence and solitude.

In this reflection, we look at one such model, Thomas Merton, who, like us, had “feet of clay,” yet followed his deep call in a conversion journey to in-depth silence, solitude, and contemplation.

40th Anniversary

December 10, 2008, marked the 40th anniversary of Merton’s death. A Renaissance man, world traveler, lover of literature, poetry, music, and languages, he became a Catholic in 1938 and then joined the Cistercian monastery (Trappists) on December 10, 1941. He had hoped to enter the Carthusian order of hermits but there were no monasteries in North America, and with World War II raging in Europe, he knew it was unwise to go there. Instead, he entered the Trappists.

Merton lived as a priest-monk at Gethsemani, Kentucky, paradoxically deepening his inward journey of silence and solitude, becoming a mystic, spiritual leader, pacifist, prophet, as he became a more prolific writer, poet, scholar, theologian, photographer, teacher, political activist.

By nature garrulous and loquacious, Merton was not your stereotypical monk. With his autobiography, Seven Storey Mountain, published a short time after he entered the Trappists, Merton became known worldwide as a model and mentor for countless people searching for “the real” in life. Twenty-seven years to the day he entered Gethsemani, Thomas Merton died of accidental electrocution in Bangkok, Thailand. He was there as one of the seminal speakers at a meeting of East and West monks, Sisters, and abbots, all searching for common ground in their common search for the mystery of God.

Silence

When Merton entered the Trappist monastery, he was well aware of its silent lifestyle. He was also aware of his gift, desire, even need, to communicate, yet he resolved to become a silent monk. Silence, at this juncture in his life was an either/or dynamic: silence and speaking (writing) were dualistic opposites. The lived reality of this exterior silence was demanding on most of the monks and, it would seem, particularly on Merton. Even the Trappist sign language, used for purposes of necessity and charity, was creatively used and expanded by Merton to the point where stories were told about his being the most un-silent silent monk in the monastery.

“I shall certainly have solitude. Where?

Here or there makes no difference.

Somewhere, nowhere, beyond all ‘where.’

Solitude outside geography or in it. No matter.”

Thomas Merton

Gradually, Merton saw the need and necessity of this exterior silence as the disciplinary practice of refraining from unnecessary speech in order to foster patience, equanimity, charity, and interiority. It became the initial step to interior silence, the silencing of one’s heart for that “all encompassing silence of a mystical experience...an experience that is ineffable...”(John Teahan, The Message of Thomas Merton, 1981). Merton’s daily contemplation contributed to the maturation of his thought on both exterior and interior silence as a positive, creative source out of which merged the word/Word as an expression of the truth within himself and God.

Solitude

Benedict, the Father of Western monasticism (480-547 A.D.), was initially a hermit, but over time, when disciples came to join him, he moved from the solitary, eremitical life to a communal lifestyle. When Merton entered the Trappists, the communal or cenobitic antithetical to communal life.

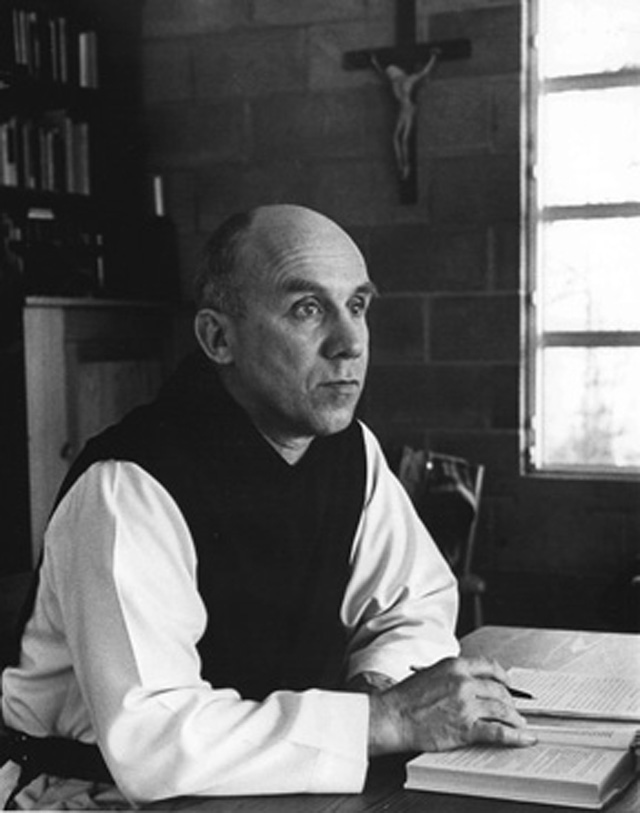

Photograph by John Howard Griffin: Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University, Kentucky.

Photograph by John Howard Griffin: Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University, Kentucky.

From the very beginning, Merton felt called to the hermit life, a vocation within a vocation. He spoke of his in-depth desire for more intense physical and interior solitude, a desire that deepened in his years as a Trappist. He researched this aspect of the Trappist life and wrote prolifically about it, only to have these writings strongly censored by his Cistercian order. Despite these many setbacks, Merton’s determination and hard work resulted in the eremitical life being restored in 1964 at a meeting of Cistercian abbots of North and South America held at Gethsemani. Now, hermitages would be integral to Trappist monasteries, available to those who felt called to the solitary life. On August 17, 1965, Merton became the first official hermit of the Cistercians since perhaps the Middle Ages.

Contemporary Hermits

Forty years on, both the desire and need for silence and solitude have burgeoned in ways Merton intimated in his writings. Midst rampant consumerism, narcissism, noise pollution, and seeming lack of religion and/or spirituality, contemporary hermit life is growing beyond any specific geography. Women and men, lay and religious are living this vocation, many without the support of formalized structures.Contemporary hermits, variously called recluses, lay hermits, marketplace hermits, urban hermits, forest dwellers, live their own rhythm of silence, solitude, and contemplation in the midst of their daily lives. Called into silence and solitude for a period each day, a time each week, or full-time, today’s hermits gradually develop their own unique rhythm, a rhythm that informs how they live their lives.

Steeped in a desire for right relationships with all life, one can find contemporary hermits involved in peace and nonviolence vigils, fasts, eco-justice issues, as well as a caring presence in the neighbourhoods of their own specific geographies. Some form support networks through such publications as the quarterly newsletter, Raven’s Bread, which focuses the different issues, concerns, and insights of many contemporary hermits from around the world.

Thomas Merton, in his life of many twists and turns, followed his deepest desire, that of becoming a full-time hermit. He is a model for us about keeping a dream alive. On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of his death, we can remember Merton’s passion for following his deepest desires. Like us, he often said he wanted to live into God’s deepest desires for him. Still Merton trusted in God’s wisdom and love for him even when he was not sure of the way. We also know from deep within, God’s deepest desires for us are our deepest desires. And we make the way by walking even when we are not sure of the way.

Janet Malone, a member of the Congregation of Notre Dame (CND), is a skills trainer, workshop and retreat facilitator, and author of the book, “Transforming Conflict and Anger into Peace and Nonviolence”, published by Novalis ISBN: 9782895076926 (2007).

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article