Table of hope

By José Robelo

January/February 2009

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

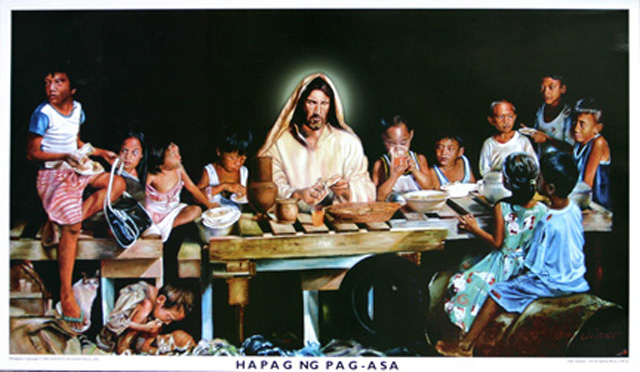

Overnight, Joey A. Velasco became a well-known artist in the Philippines. Barely six months after taking up painting at age 38, Velasco rendered the above scene of Jesus at supper with street children. He entitled the work Hapag ng Pag-asa, or “Table of Hope.”

Velasco regards his newly discovered talent as God-given. “I am only the paintbrush,” he says. His portrayal of underprivileged children radically changed his life and the painting that gained him fame became a symbol of the fight against extreme poverty in the Philippines.

Joey Velasco, who became a well-known artist in the Philippines after his rendition of Jesus at supper with street children, shown here.

Joey Velasco, who became a well-known artist in the Philippines after his rendition of Jesus at supper with street children, shown here.

An entrepreneur at age 21, Velasco had built a manufacturing business with 30 employees, when suddenly in 2005 a serious kidney problem brought him to a hospital for major surgery. “During my three-month convalescence at home,” he says. I felt the urge to create figures of what I had experienced in the hospital, so I started scribbling, dabbling, sketching, but everything was so crude.”

With his wife Queeny overseeing the business, Velasco bought art books and searched the Internet to learn how to do portraits. Then he learned that Norman Sustiguer, a teacher of fine arts at the University of the Philippines, had just retired and moved into his neighborhood. “I was lucky to become his student,” he admits. “I learned by doing. I started painting portraits of my wife, my four children, anything that caught my fancy.”

But the principal inspiration for the painting that gained him fame came from the eating habits of his children—Marco, age 11, Chiara, eight, Clarisse, five, and Marti, four. My kids were complaining about their food and becoming choosy,” he explains. “So, I thought of providing them with a visual reminder, strong and challenging, of their blessings of life and to appreciate what was on the table.

“My kids were complaining about their food and becoming choosy,” he explains. “So, I thought of providing them with a visual reminder, strong and challenging, of their blessings of life and to appreciate what was on the table.”

To find models, Velasco went to different squatter areas of Manila, under the bridge and to the North Cemetery, where families live amid the tombstones. “I fed the kids noodles and juice, and when they were not looking, I took photos,” he says. In 45 days, he completed the 4-by-8- foot canvas, which he put on his dining room wall.

He entitled the work Hapag ng Pag-asa, or “Table of Hope.” Photo inset: Velasco with a Filipino living in the United States who donated land in the Philippines to build houses for the poor.

Asked about the reaction of his children, the artist replies, “I don’t have to talk anymore. The painting talks to them.” He was brought up short, however, when his offspring asked the names and identity of the children in the painting. “I had no answer,” he says, admitting his chagrin. “I just used them as models. I didn’t know them personally.”

That would change. When a priest friend, Monsignor Romulo Raňada, saw the painting, he was so impressed he suggested unveiling the artwork at the close of the National Eucharistic Year at the cathedral in Manila. Velasco agreed. People flocked to see it. The work was publicized in newspapers, on television, and over the Internet. Charitable organizations asked if they could print and sell copies to raise funds for poor children. The surprised artist complied.

He entitled the work Hapag ng Pag-asa, or “Table of Hope.” Photo inset: Velasco with a Filipino living in the United States who donated land in the Philippines to build houses for the poor.

He entitled the work Hapag ng Pag-asa, or “Table of Hope.” Photo inset: Velasco with a Filipino living in the United States who donated land in the Philippines to build houses for the poor.

The fame, however, began to bother him. “I didn’t paint it for the public, just for the house,” he says. “People told me they liked the beauty of the painting, the realistic aspect. I was feeling proud. Then little by little I came to realize that the painting showed more meaning than even I thought about as I was painting. I was no longer looking at the painting. The painting was looking at me. The subjects of my painting were observing me. I could no longer escape them. They became missionaries to me, and took me on a spiritual journey.”

Using his photos, he retraced his steps to the squatter areas, the bridge and the cemetery. “I searched for each one of them, and it was only then, when I knew who they were, was I able to find myself and my God. I thought they were the ones who were lost, only to find out I was the one actually lost. From those children I learned what they were doing every day, who their parents were, and things I never learned in school, like the nobility of character, courage, and faith in the face of unspeakable poverty.”

Velasco also says the experience changed his image of God. “In my encounter with the children,” he explains, “I realized that God is not a far God, but a near God, someone who is offering love for free. If you notice the children in the painting, they are not looking at Jesus. I began to realize that Jesus cares even for those who do not bother with him. I did not pay attention to God for a very long time, but God paid attention to me because of his uncondi-tional love.”

Before, he says, the faces in his painting were anonymous. Now, he can answer his own children: “I can tell them which one is Itok, which one is Nene, Joyce, Tinay, Emong, Onse, Buknoy, Michael, Doday, Jun, Roselle or Sudan.”

Fr. Jose Rebelo, a Comboni Missionary of the Heart of Jesus, is editor of World Mission, an Asian Catholic magazine published by the Comboni Fathers. The above story was adapted for Maryknoll magazine from an interview with the artist in World Mission. Reprinted with permission.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article