Remembering Bishop Ruiz 1924-2011

By Fr. Ron MacDonell, S.F.M.

March/April 2011

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article

I think you will have to walk, you're too tall to ride on a donkey," Bishop Samuel Ruiz said to me. He had arrived in the town of San Juan del Bosque, tucked away in the hills of Chiapas, Mexico, where I worked as a lay missioner in the early 1980s. I was to accompany him to a Tzotzil village where he would celebrate the sacrament of confirmation. It was an arduous trek to the vil-lage, involving an hour's hike down a steep incline to the bottom of a gorge, then crossing a river on a wooden slat bridge, and finally climbing up to the village. Bishop Ruiz chose to ride on a donkey. I was keen to go on foot, and so I took off with the catechists. The confirmation celebration with the young Tzotzil Mayan people was both serious and joyous, their faces illuminated by happiness at receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Later, back at San Juan, Bishop Ruiz observed: "You climbed fast! I had barely started the climb back when I looked for you, and there you were, almost at the top of the cliff!" Indeed, I wanted to do everything fast in those days, in my mid-20s. During my two years in Chiapas, I learned to slow down and walk at the pace of the people. I learned from this bishop who rode on a donkey, like Our Lord riding into Jerusalem. I observed the cross of oppression: indigenous peoples exploited by landowners, the men beaten and the women abused, the coffee beans bought at a cheap price. I observed death: leaders assassinated, children dying of malnutrition. I witnessed the light of the resurrection, shone forth by the Church which opted to speak for the poor, in particular the indigenous peoples. Bishop Ruiz was our pastor, beloved by the people, who called him "jtotik" (our father).

I learned much in the bible courses I participated in with the people. Once we hiked nine hours to a remote village and spent five days studying the Gospel of St. Mark with new catechists. During the course, we experienced a communal feeling, sharing our food of beans, tortillas, and peppers, enduring the heavy heat of the afternoon, sleeping on the wooden planks that served as church pews. As we read each gospel chapter, we answered four questions: What did Jesus do? Who were his friends? Who were his enemies? Is the situation similar to our reality today?

Our reflections convinced us that the Good News of Jesus Christ is liberating. He invites us to denounce social injustices and to proclaim a world of justice and peace. "I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full" (John 10,10).

Bishop Ruiz spoke clearly about this full life, this dream of Jesus where all of us live like brothers and sisters, where economic exploitation no longer exists, where there is no more racism or division based on hatred or prejudice. Bishop Ruiz inspired many missionaries to come and work alongside the local church leaders to make the dream a reality. A program for permanent deacons was created for indigenous church leaders. Cooperatives for coffee growers were founded. Women's sewing centres were set up, and so on. We will sadly miss this great man, but we rejoice with the legacy he has left us. Muchas gracias, jtotic!

“Being a prophet is nothing more than making our life a witness to what we believe in. This is what it means to proclaim the Reign of God...we might be asked to dedicate ourselves and take more responsibility for important things in the process of change. This requires giving testimony, and with this might even come persecution.”

Bishop Samuel Ruiz, "Seeking Freedom", published by the Toronto Council of Development and Peace, 1999.

In solidarity with the people of Chiapas

In the early 1980s, Scarboro missionaries worked in Chiapas, Mexico, and experienced firsthand the plight of the Mayan people. The bishop of the diocese of San Cristobal de las Casas at that time was Samuel Ruiz Garcia who invited us to come. From the very beginning Bishop Ruiz stood in solidarity with the people. His support of their cause eventually led the Mexican government to force the Vatican to remove him from Chiapas.

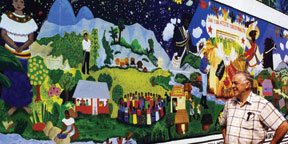

Fr. Charlie Gervais, one of the organizers who helped bring the Taniperla mural to Scarboro Missions.

Fr. Charlie Gervais, one of the organizers who helped bring the Taniperla mural to Scarboro Missions.

On January 1, 1994, Chiapas, Mexico's southernmost state, drew international attention after an uprising by Zapatista rebels. Descendants of the Indigenous Mayan peoples, they were protesting centuries of exploitation made worse by the North American Free Trade Agreement. The rebellion led to the militarization of the area and along with that, intimidation, assassinations, and a massacre of villagers such as at Acteal when 45 Indigenous men, women, and children were killed by paramilitaries on December 22, 1997.

Taniperla mural

In 1998, a mural was unveiled in the town of Taniperla in Chiapas. The mural depicted Mayan traditions and ideals of community life, and represented peace, harmony, unity, and happiness. It was designed and painted over a period of four weeks by members of 12 Indigenous communities in the area as part of a communications workshop with university professor Sergio Valdez Ruvalcaba.

The day after the mural was unveiled, Mexican armed forces occupied Taniperla and covered the mural in white paint. They arrested Professor Valdez along with a human rights activist, Mr. Luis Menendez Medina, and five Indigenous participants. The actions of the security forces were perceived as an attempt to destroy the municipality's autonomy.

In an act of international solidarity, the Taniperla mural was recreated in Argentina, Brazil, Spain, Italy, Ireland, San Francisco, Mexico City, and in Canada at Scarboro Missions. The mural, titled "Greeting to Taniperla," was a community art project. In addition to the original design, it also includes images representing issues affecting Toronto communities. Local artists Claire Carew, Hannah Claus, Sady Ducros, Lynn Hutchinson, Raffael Iglesias, and Shelley Niro, worked with 16 students from two Scarborough area high schools (Winston Churchill Collegiate and Alternative Scarboro Education 2) and with children from five Toronto elementary schools. The mural imagery was workshopped at A Space Gallery, a Toronto nonprofit art gallery, and then painted on the walls of the handball courts at Scarboro Missions.

Professor Sergio Valdez Ruvalcaba who had been imprisoned, and a young Mayan activist, Nicolas Gomez Perez, came from Mexico to be present at the mural's unveiling on July 2, 2000. About 250 people took part in the event, which included an interfaith prayer service with members of the Baha'i, Jewish, and Sikh faith traditions. As well, there was a Mayan ritual and dancing, with the troupe made up of Mayans who had immigrated to Canada.

Adapted from "Greeting to Taniperla" by Fr. Charlie Gervais, S.F.M., Scarboro Missions, March 2001.

Return to Table of Contents

Print Article